Examples of Solving Problems Using the Cube Strategy

Not long ago, Square CEO Jack Dorsey challenged his team to create a solution for accepting payments at Starbucks, which the mobile-payments company had partnered with in August. When an engineer worked out a solution (using QR codes within the Square Wallet app that could tap into Starbucks' preexisting system), Dorsey was so giddy that he grabbed a high-end bottle of scotch off his desk and gave it to the engineer as a reward. The only catch? As both would soon learn, the bottle of alcohol was worth a lot more than Dorsey had initially realized–roughly $2,000.

Now, as the tale around the office goes, every time Dorsey retells the story, the price of the bottle keeps shooting higher and higher–an anecdote Dorsey facetiously uses to highlight his unmatched generosity toward employees. "It became like Gob's suits in Arrested Development," the engineer told me with a smile on a recent visit to Square's headquarters.

It's a funny story, sure, but it also serves to show what's rewarded at Square: problem solving. Though Square is often lauded for its culture of design, that understanding overlooks a simple truth. "We're not just a design company; we're not just an engineering company," says CTO Bob Lee. "We're strong in both areas–we need to be." And part of what's made Square such a success story is its ability to cultivate a collaborative atmosphere for designers and engineers–a DNA of problem solving that unifies its various product groups.

Since the service launched several years ago, Square has become as much known for its industrial design as for its dead-simple digital services, which include Square Register and Square Wallet. Its secret sauce has been ridding pain points from the traditional process merchants had to endure to begin accepting payments at their businesses. That commitment to simplification–a commitment Square COO Keith Rabois once referred to as being "obsessive compulsive"–is the result of blurring the lines between design and engineering. As Lee, an engineer who also has a design background, puts its, "From an engineering perspective, design is not just about how something looks, but about how something works. We look at reliability, robustness, and performance as features of the design." That thinking has paid off, too: Square now processes $10 billion in annualized payments.

Thus, Dorsey can afford to reward his employees with a nice bottle of scotch or two–likely a better incentive for good work than what he used to offer. "This is true: For my signing bonus at Square, Jack gave me a bag of Reese's Pieces," recalls Square creative director Robert Andersen, one of the company's earliest employees.

"Oh, Reese's Pieces? I thought I offered you Skittles," Dorsey jokes.

Square's Well-Rounded Aesthetic

Late last year, web design lead Geoff Koops sat in an interview opposite Jack Dorsey. He was considering leaving Apple for Square, but before that was even option, he had to clear this most important hurdle in the interview process. "He'd ask me these big questions–like, 'What is design?'–then sit back with his impeccable posture and watch me flounder," Koops says. "He kind of observes you, without giving that nodding, smiling feedback that keeps you going. I was nervous."

But not nervous enough to throw a tough question back to Dorsey when the time came. "I asked him very specifically for his thoughts on skeuomorphic design," recalls Koops, referring to when an object retains ornamental or decorative elements of past versions of that object–say a digital writing application modeled after a real-life yellow legal notepad, complete with margins and paper tears.

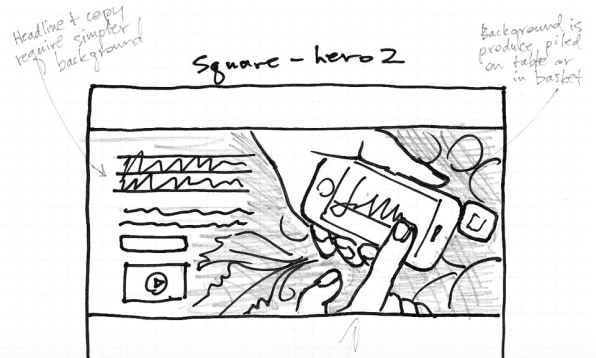

The debate around skeuomorphism exploded in the last year, but at Square, it was arguably a blip on the radar, at least in the public's eye. The company's original leather-textured wallet app was redesigned in March with a simplified interface sans skeuomorphic elements. Since then, Square has managed to rally its teams around a unique aesthetic: a minimalist grayscale color scheme, high-res imagery, playful interactions, and subtle animations. Square's distinct design DNA–which Andersen calls "a combination of simplicity, straightforwardness, and cleanliness"–is identifiable across its hardware, apps, and websites, a feat few startups accomplish so early on. "We try to keep everything related to each other across our products and videos and marketing–they should all speak to each other," Andersen says. "We hold each other accountable for designs that seem arbitrary at Square."

Toward this end, it's partly Andersen's job (which he refers to as "chief collaborator") to make sure all the groups at Square speak the same language. ("It's not my job to tell everyone what to do, though I of course have strong opinions," he laughs.) The startup holds weekly all-hand meetings–called Town Square–where everyone from engineers to PR workers can show off their latest projects; the design teams also hold regular creative reviews. The gatherings are crucial to making sure the various groups are on the same page. When I ask Lee whether his engineers could define skeuomorphism, for example, he responds, "Absolutely, absolutely."

Koops says it's about "internal education." Otherwise, as Andersen says, "the left hand wouldn't know what the right hand is doing."

It may sound simple, but as companies grow, this becomes increasingly difficult to scale, and can have tremendous impact on a company's culture and aesthetic. At the extreme end, just look at a company like Microsoft, which for some time seemed to be driven by disparate product thinking: It would be hard to tell that Windows and Xbox were created by the same company, in other words. It may explain why Square appears so committed to cross-pollination and self-review–especially as the company starts to move to its new headquarters next summer, plans to grow to 1,000 employees, and continues to acquire startups as it did with design studio 80/20.

In early November, Andersen took me to Square's creative review space, which looks like a yoga studio or, as one employee puts it, an "art gallery." Here, Andersen says part of his job is to "keep everything in sync."

"Even though our Register and Wallet teams are technically separate–they report to two different people–it needs to be an integrated system, so information sharing is really important," he says.

Senior interaction designer Mia Blume describes a typical review. "We pin up all our work on the wall and share with other designers to get fresh perspective," she says. "We get so close to the product that it's really hard for us to step back and look at it. There are 100 different ways to solve a problem."

"That's actually something I used to do a lot at Apple, and something I do a lot here now," Koops says. "People naturally form a semi-circle around the work, and there's something democratic and academic about that. It feels like an art critique."

These reviews were helpful in dealing with the internal debate around skeuomorphism, which still percolates inside Square. Says Andersen, "We learned a lot of things both from what we missed from the leather-bound app and things that had been improved with our new UI. These thoughts and lessons will influence the future of that product–though it's not that we're specifically going away from any category."

The more significant point here is that the company seems to take a democratic approach to problem solving. "If it were just one person's job, that would be both impossible and single point of failure," Andersen explains.

Lee says his team of engineers are a "first-class part of the conversation," likely because the company hires hackers who also have a good sense of design. "We look for engineers here who have that sense of product you really need to achieve a level of polish, because if you don't have an engineer that notices those details, it will just be too arduous for the designer to nitpick every little thing," Lee says. "I would say that engineering really is all about design. Even when I'm designing an API, for example, I think of it as a user interface."

Still, that doesn't mean leaders like Dorsey and Andersen don't often drive Square's design through their own strong points of view. As Koops recalls of his question to Dorsey about skeuomorphism, "I remember Jack made a convincing argument [in my interview]–he immediately had five really salient thoughts top of mind."

Adds Lee, "Jack fundamentally believes these details are important; he's equal parts design and engineering."

Receipts Can Be Sexy

Ever dreamed of working under Jack Dorsey's direction at Square? For a startup as sexy as Square is in the Valley, the company is tackling some rather unsexy problems: credit card processing, receipts, point-of-sale systems. "Jack is a big fan of trying to make the mundane feel fun and whimsical and interesting, even a refund screen, for refunding credit-card payments,"Andersen says. "He calls us out on that kind of stuff all the time. Some people when they hear that are like, 'Oh my god, that's not helpful at all. I don't understand why this should be fun.'"

I don't blame them. I'm with Andersen in the center of Square's offices, in between the rows of iMac-lined desks that separate the startup's dining area and in-house coffee shop. With Dorsey standing close by with a group of employees, I can't help but draw a blank in imagining how to redesign a refund screen into something that's fun, let alone whimsical. "Well frankly, this industry has been neglected for so long that even putting in a modest amount of thinking in terms of modern user experience makes this stuff way better," Andersen says.

He points to Square's rethinking of receipts. "People don't like paper," he says. "Whenever I get a receipt, I cram it into my pocket and throw it away. It's such a waste. So when we think about making this more fun, we first think about taking the pain out of it. Like you know what? A receipt should have beautiful photos of items on it; maybe it should actually come with a description. Now our receipts just push directly to your phone. Fun also comes from usefulness–people get bogged down by things they think are trash."

Mia Blume ticks off the industry's myriad headaches. "For a lot of traditional POS systems, [merchants] have to spend thousands of dollars, and get someone to go out and program it for them. There's a lot of setup time, and it's very static. Once they've set it up, they can't really change it themselves. It's overly complex and time-consuming." Hence, for SMBs, it's perhaps fun just being able to accept a signature on an iPhone or customize an inventory list on an iPad.

"That stuff is very challenging to implement…design is more than the way things look," Lee says. He recalls working with Andersen on everything from authorizing payments over a network to verifying account funds to determining when to send a user his or her receipt. "Do you send the receipt information before or after taking the signature?" he says. "You have to consider this kind of stuff."

Often, merchants won't even notice all the clever elements the Square team embedded in its services. "People appreciate design on different levels, so I think the stuff that you pick up on isn't likely the same as the pizzeria owner in Iowa," says Koops. "But everybody notices good design, and I think everybody benefits from it. There's no wasted effort here."

Sweat The Small Stuff

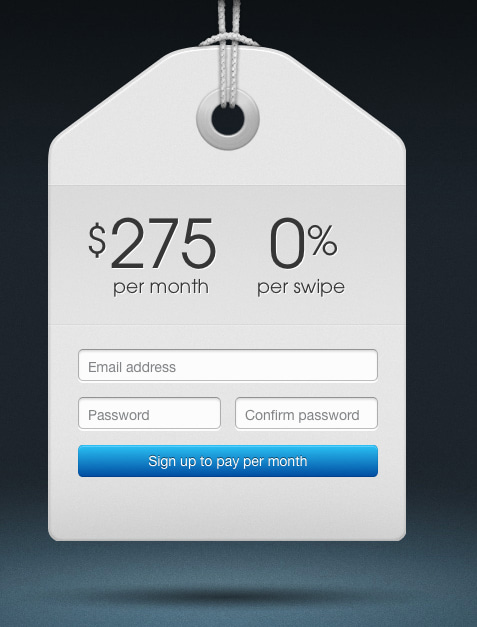

No wasted effort? I'm sitting with Koops in one of the cabanas at Square, where the designer is, in great detail, describing a slight drop shadow resting below an image of a price tag on the company's website. When the price tag sways–ever so subtly, for only a moment or two–the shadow underneath follows its path, back and forth. It's an elegant animation, though hardly noticeable–if you blink you might miss it. "That really came to life in the hands of the engineers," Koops says. "And the shadow actually matters to that pizzeria owner in Iowa."

He's being serious.

The level of detail is common of Square's team, which pays its products pixel-close attention. Once, for example, the team urged Fast Company to change an image we featured in a Square story about Starbucks because it contained the incorrect rendering of the picture's green coloring. ("It's subtle," the PR rep wrote to me then by email, "but the green at the top is [fashioned after] a [Starbucks] apron [material], versus just being green and flat.") And that sense of detail stretches to the highest levels of the company.

Koops cites the time when Jack Dorsey and Robert Andersen were looking over a redesign of the company's website. The site would soon relaunch, and the two were staring at one image on the company's website: an iPad, sitting atop a metal stand, running Square Register. "Jack said, 'That's weird–it looks like a wonky iMac or something,'" Koops recalls. "Once I saw that, I couldn't un-see it. It was ilke, 'Oh, you're right.'"

Koops and his team had spent months drafting designs for the new website; detailing the page's layout; and enlisting top-notch photographers for the site's images. Now, Dorsey was questioning the site's launch due to this one, inconspicuous metal stand. ("And this was like a $10,000 photograph…whoops!" Koops says.)

"So we came up with this idea of taking a plywood Eames chair, and repurposing it into this stand–this stand that never actually existed," Koops explains. "Just changing the material was enough to remove that potentially bad perception–that confusing perception [that an iMac was required to use Square]."

Adds Koops, "That's one of those awesome little details that I don't think would've been bothered with elsewhere."

Not even at pizza shops in Iowa.

Examples of Solving Problems Using the Cube Strategy

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3004037/solving-problems-square-way

0 Response to "Examples of Solving Problems Using the Cube Strategy"

Post a Comment